A Meditation on Modern Cruelty

After Eduardo Galeano’s “The Nobodies”

They are not human beings,

they are human resources.

They do not have names,

they have productivity metrics.

They do not have faces,

they have employee ID numbers.

They do not have hearts,

they have performance indicators.

Eduardo Galeano’s poem “The Nobodies” pierces through the comfortable abstractions we use to distance ourselves from human suffering. In its stark repetition, it reveals how modern systems transform people into categories, individuals into statistics, and pain into acceptable externalities. But Galeano’s vision, written decades ago, has evolved into something even more insidious in our contemporary moment: we have built a machinery of indifference so sophisticated that it operates without malice, so efficient that it barely requires conscious cruelty.

The Architecture of Abstraction

Modern society has perfected the art of making suffering invisible through layers of abstraction. We speak of “market corrections” rather than families losing their homes. We discuss “labor optimization” instead of communities destroyed by factory closures. We analyze “demographic transitions” while people flee wars we barely acknowledge. The language itself becomes a buffer, creating distance between decision-makers and consequences, between the comfortable and the expendable.

This linguistic sleight of hand serves a psychological function as much as a political one. When a pharmaceutical company prices medication beyond the reach of the dying, executives sleep soundly because they are “maximizing shareholder value.” When a social media algorithm amplifies hate speech because it drives engagement, engineers rationalize it as “user preference optimization.” The suffering is real, immediate, and measurable, but the responsibility is diffused through systems so complex that no individual feels accountable for the human cost.

The efficiency obsession that defines our era has transformed this indifference from a moral failing into a virtue. To pause and consider the human impact of our decisions is seen as inefficient, unprofessional, naive. The manager who agonizes over layoffs is less valuable than one who can execute them cleanly. The doctor who spends time comforting patients is less productive than one who processes more cases per hour. We have created incentive structures that systematically reward the suppression of empathy.

The Cruelty Inheritance

But beneath these institutional failures lies something more troubling: the persistence of human cruelty across all attempts at moral progress. The armed conflicts ravaging our world today follow patterns established thousands of years ago. In Ukraine, Gaza, Sudan, Myanmar, and countless other places, human beings wake up each day and choose to inflict suffering on other human beings. They do so not despite their humanity, but because of it.

This cruelty is not random or inexplicable. It follows a logic as old as our species: the logic of payback, of transferred pain, of suffering seeking outlet. The person humiliated by their superior finds someone weaker to humiliate. The community traumatized by violence becomes willing to traumatize others. The nation that has been invaded becomes, when strong enough, an invader. We pass our pain down like an inheritance, each generation finding new ways to make others pay for what was done to them.

Modern life has not eliminated this dynamic but has made it more sophisticated. Our frustrations are more diffuse—traffic jams, automated phone systems, bureaucratic mazes, jobs that feel meaningless. None of it is dramatic enough to justify real rage, but it accumulates into a background resentment that seeks expression. The road rage incident, the cruel comment on social media, the casual workplace bullying—these are not aberrations but pressure valves in a system that generates more frustration than it knows how to process.

The Adaptation of Numbness

Perhaps most disturbing is how indifference becomes a survival strategy. Healthcare workers learn not to get too attached to patients who might die. Social workers develop emotional barriers to protect themselves from the endless parade of human misery. Politicians master the art of discussing mass suffering in abstract terms because the alternative—feeling it all—would be paralyzing.

This numbness serves a function, but it comes at a cost. The protective callousness that helps us navigate a cruel world gradually becomes genuine indifference. The executive who starts by reluctantly cutting benefits to save the company ends up seeing employees as line items on a spreadsheet. The soldier who learns to dehumanize enemies to survive combat struggles to see civilians as fully human afterward.

The adaptation becomes the identity.

We have built economic systems that reward this emotional numbness. The most successful leaders are often those who can make decisions without being burdened by empathy. They advance not despite their indifference to suffering but because of it. Meanwhile, those who remain sensitive to human cost find themselves at a systematic disadvantage, gradually filtered out of positions where they might make a difference.

The Persistence of Patterns

Look at the armed conflicts tearing apart our world, and you see the same dynamics Galeano observed in economic exploitation applied to violence. The victims become statistics, their names unknown, their faces unseen. A hospital becomes a “military target.” A school becomes “collateral damage.” Children become “enemy combatants.” The same abstraction that turns workers into resources turns civilians into acceptable losses.

These conflicts reveal something uncomfortable about human nature: our capacity for systematic cruelty seems inexhaustible. We have international laws, human rights frameworks, global communication that makes suffering visible, and yet the violence continues. Each generation discovers new ways to inflict ancient forms of pain. The tools evolve—from swords to drones—but the willingness to use them against other humans remains constant.

What makes this particularly disheartening is how quickly victims can become perpetrators. The oppressed, when they gain power, often replicate the systems that oppressed them. The colonized become colonizers. The abused become abusers. The pattern suggests that cruelty is not a deviation from human nature but an expression of it, waiting to emerge whenever conditions permit.

The Illusion of Progress

We tell ourselves stories about moral progress, about civilization advancing toward greater compassion and justice. And there is truth in these stories—slavery is now universally condemned, democratic ideals have spread, human rights discourse has global reach. But these advances exist alongside unchanged patterns of cruelty and indifference. We have become more sophisticated in our methods, more subtle in our violence, more efficient in our exploitation.

The plantation becomes the sweatshop. The colonial administrator becomes the international development expert. The inquisitor becomes the algorithm that decides who gets healthcare. The forms change, but the fundamental dynamic persists: some humans deciding that other humans are expendable in service of larger goals.

Perhaps the most honest conclusion is that the brief periods of peace and cooperation in human history are the anomalies, not the norm. The moral frameworks we construct—religions, philosophies, legal systems—are elaborate attempts to contain something that remains fundamentally unchanged within us. They work, sometimes, for some people, in some places, for limited periods. But they are always fighting against gravity.

The Acceptance of Limits

There is something oddly liberating in accepting the persistence of human cruelty rather than continuing to believe it can be eliminated. If indifference and violence are permanent features of human society rather than problems to be solved, then the question becomes not how to create a perfect world but how to minimize harm in an imperfect one.

This acceptance does not mean resignation. It means working within reality rather than against it. Building systems that assume humans will sometimes be cruel rather than systems that assume they won’t. Creating redundancies and safeguards that limit the damage any individual or group can inflict. Recognizing that moral progress is temporary and fragile, requiring constant maintenance rather than being a permanent achievement.

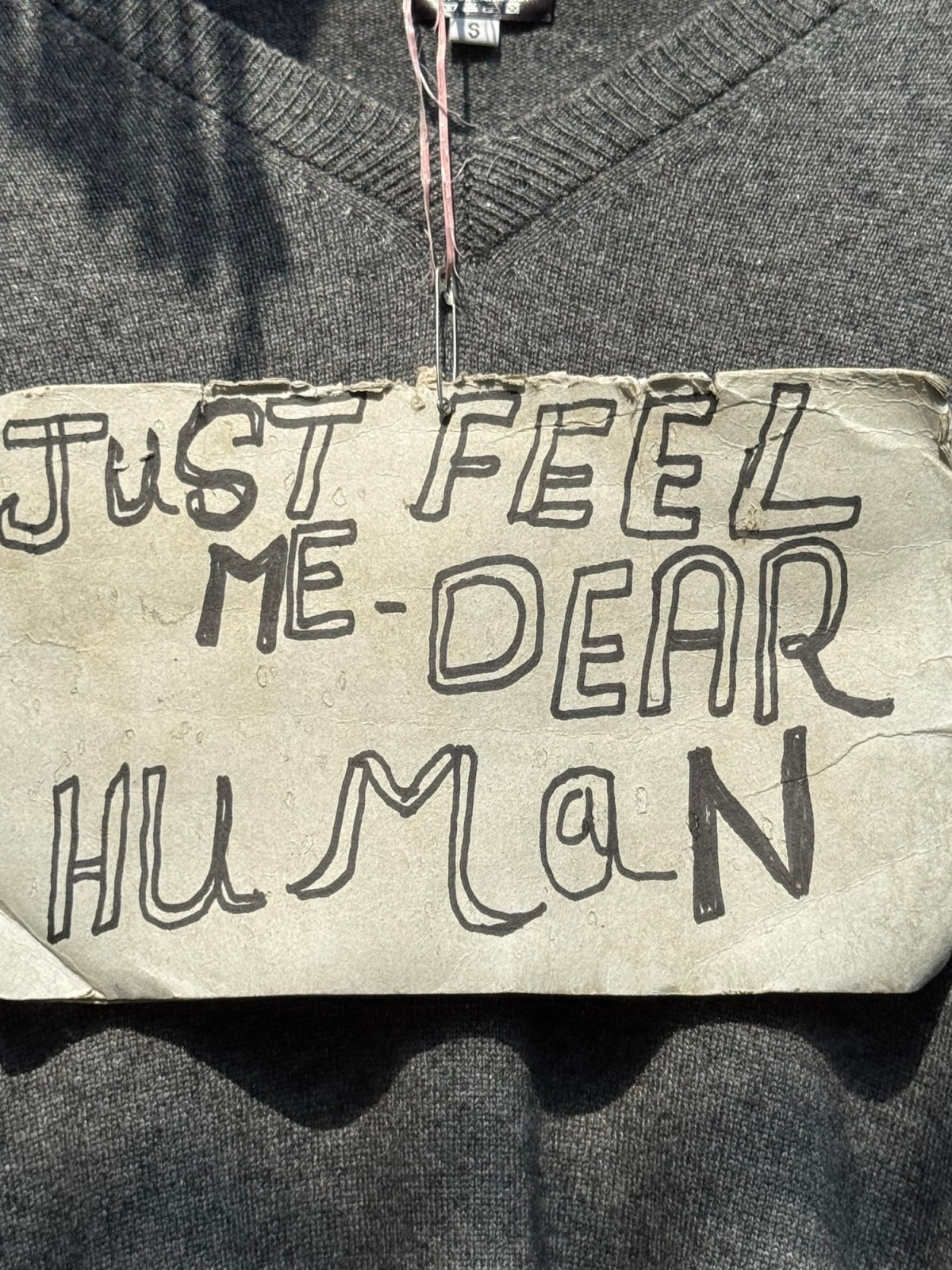

Galeano’s nobodies are still with us, multiplied by technology and globalization. They work in factories we never see, fight in wars we barely acknowledge, suffer from diseases we could cure but choose not to fund. They remain nobody not because we cannot see them but because seeing them clearly would require us to confront uncomfortable truths about ourselves and the systems we maintain.

The machinery of indifference grinds on, fed by our small cruelties and large abstractions, our inherited pain and systemic incentives. It operates with or without our consent, but never without our participation. We are all complicit, and we are all victims, caught in patterns older than civilization and seemingly more durable than any attempt to break them.

Perhaps wisdom lies not in the impossible dream of ending human cruelty but in the more modest goal of reducing it where we can, acknowledging it where we cannot, and refusing to let our necessary numbness become complete blindness. The nobodies are still nobody, but at least we can choose whether to keep pretending we don’t see them.

The nobodies (Los nadies) by Eduardo Galeano, from the book El libro de los abrazos, 1989.

Fleas dream of buying themselves a dog,

and nobodies dream of escaping from poverty,

that one magical day

good luck will soon rain,

that good luck will pour down,

but good luck doesn’t rain, neither yesterday

nor today,nor tomorrow, nor ever,

nor does good fall from the sky in little mild showers,

however much the nobodies call for it,

even if their left hands itch

or they get up using their right feet,

or they change their brooms at new year.

The nobodies: the children of nobody, that masters of nothing,

The nobodies: the nothings, those made nothing,

running after the hare, dying life, fucked, totally fucked:

who are not, although they were.

Who speak no languages, only dialects.

Who have no religions, only superstitions.

Who have have no arts, only crafts.

Who have no culture, only folklore.

Who are not human beings, but human resources.

Who have faces, only arms.

Who don’t have names, only numbers.

Who don’t count in world history,

just in the local press’s stories of violence, crime, misfortune and disaster,.

The nobodies who are worth less than the bullets that kill them.

Sueñan las pulgas con comprarse un perro

y sueñan los nadies con salir de pobres,

que algún mágico día llueva de pronto la buena suerte,

que llueva a cántaros la buena suerte;

pero la buena suerte no llueve ayer, ni hoy, ni mañana, ni nunca,

ni en lloviznita cae del cielo la buena suerte,

por mucho que los nadies la llamen

y aunque les pique la mano izquierda,

o se levanten con el pie derecho,

o empiecen el año cambiando de escoba.

Los nadies: los hijos de nadie, los dueños de nada.

Los nadies: los ningunos, los ninguneados,

corriendo la liebre, muriendo la vida…

Que no son, aunque sean.

Que no hablan idiomas, sino dialectos.

Que no profesan religiones, sino supersticiones.

Que no hacen arte, sino artesanía.

Que no practican cultura, sino folklore.

Que no son seres humanos, sino recursos humanos.

Que no tienen cara, sino brazos.

Que no tienen nombre, sino número.

Que no figuran en la historia universal, sino en la crónica roja de la prensa local.

Los nadies, que cuestan menos que la bala que los mata