These eleven films form a constellation around themes of memory, desire, and the cruel passage of time. Each represents cinema at its most emotionally penetrating, whether through the neon-soaked dystopia of Strange Days, the sun-drenched melancholy of In the Mood for Love, or the theatrical intensity of A Streetcar Named Desire.

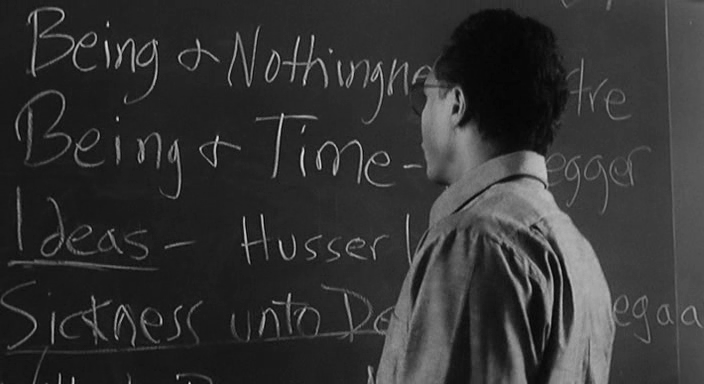

Several of these films share a fascination with non-linear storytelling and the unreliability of memory. Memento constructs its entire narrative around the protagonist’s inability to form new memories, creating a puzzle that mirrors our own struggles to make sense of fragmented experiences.

Similarly, Strange Days explores how technology might allow us to literally experience others’ memories, raising questions about authenticity and identity.

Wong Kar-wai’s 2046 and In the Mood for Love approach time more poetically, using repetition, slow motion, and careful composition to create a sense of moments suspended in amber.

The films suggest that certain experiences – particularly those involving unrequited love – exist outside normal temporal flow.

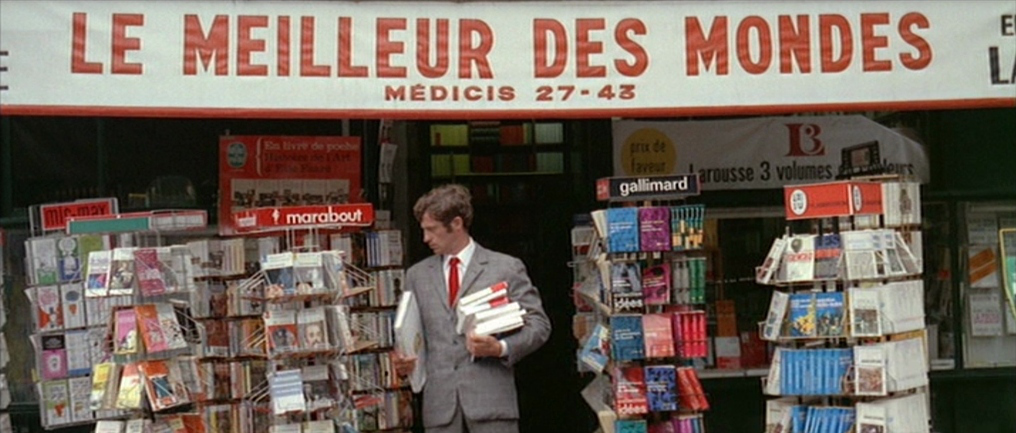

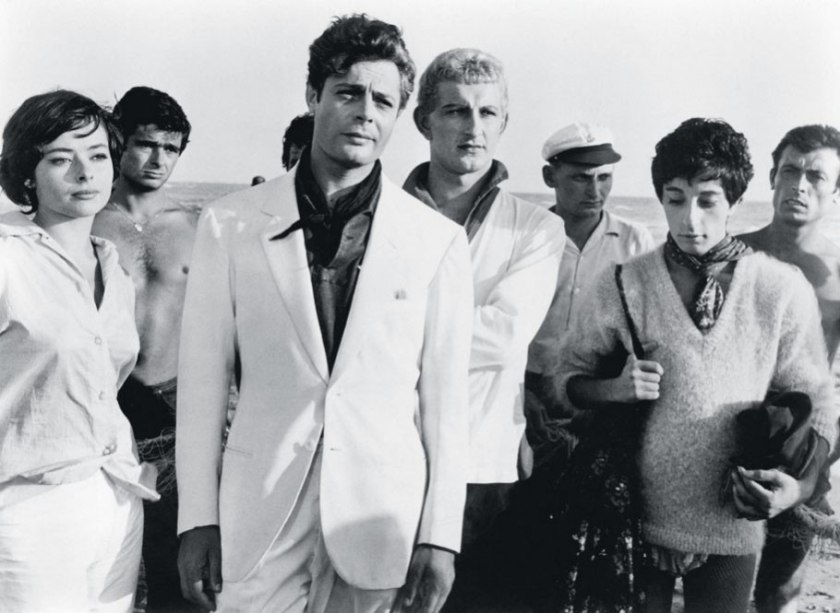

Le Mépris, Pierrot Le Fou, and Bonjour Tristesse represent different facets of French cinema’s relationship with American genre films and European art house traditions. Godard’s works deconstruct classical narrative while maintaining an almost naive romanticism about love and cinema itself.

Bonjour Tristesse, the 1958 one, though earlier, not French, and more conventional in structure, shares this tension between sophistication and genuine emotional vulnerability. I also have to say that my relation to these three movies is strongly emotional, probably because they all represent the sort of endless Mediterranean summer that I see as my “happy place”.

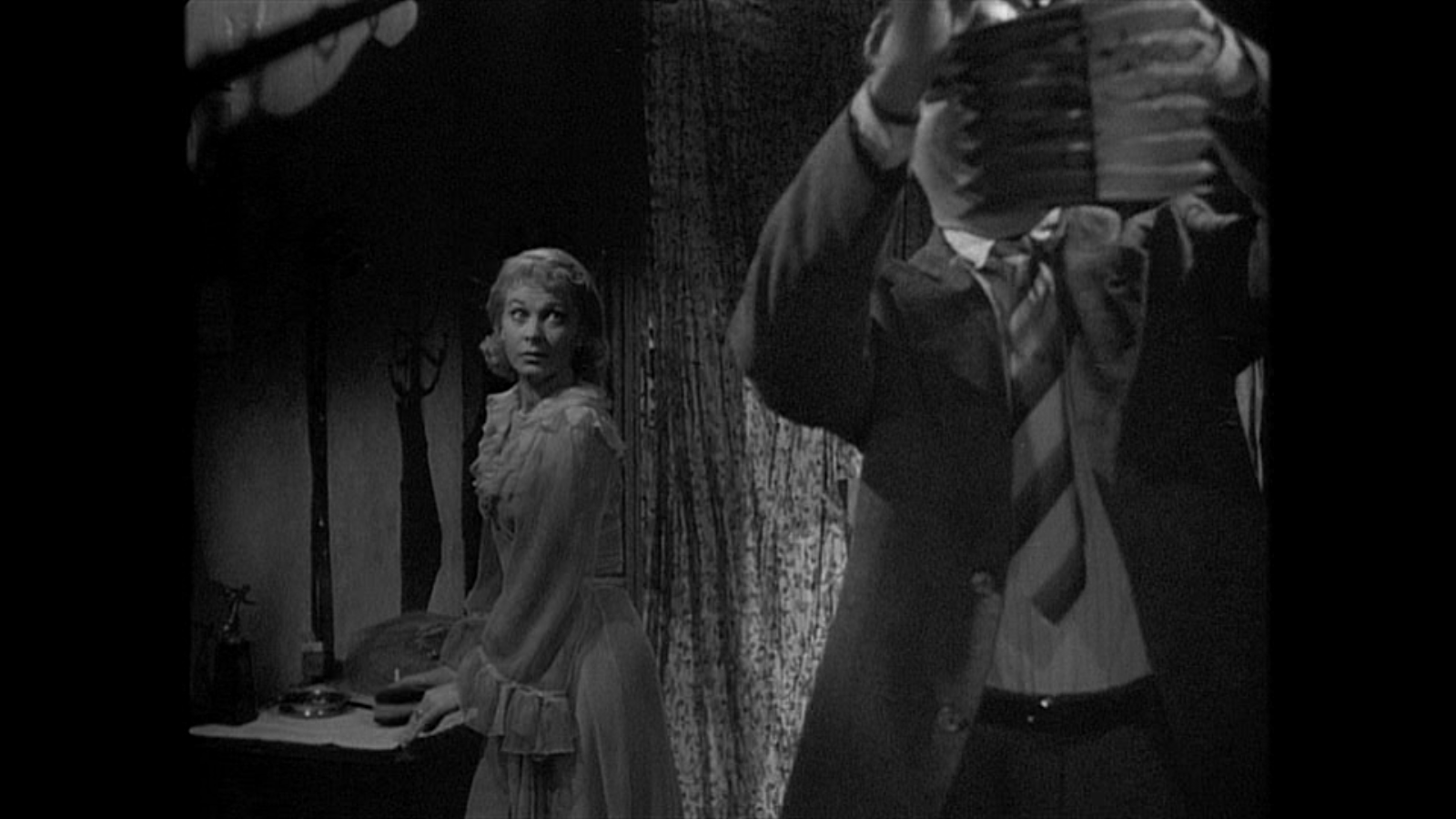

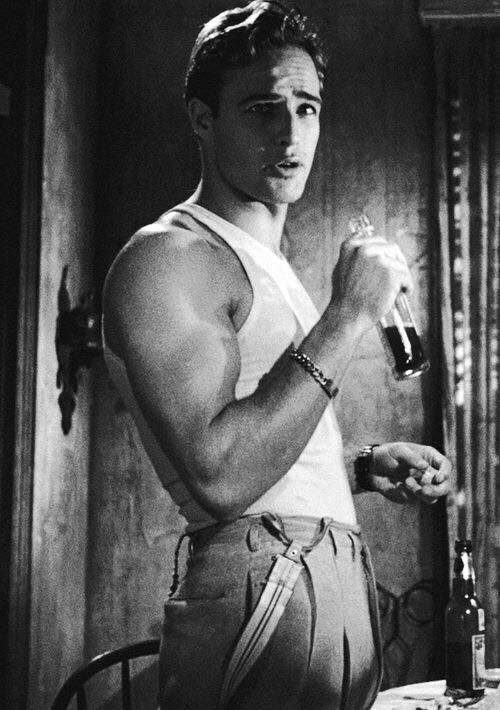

The Tennessee Williams adaptations – Suddenly Last Summer and A Streetcar Named Desire – bring a heightened theatrical sensibility to cinema. Both films explore themes of desire, madness, and social decay with an intensity that borders on the operatic. Their Southern Gothic atmosphere creates a unique American contribution to the broader themes of psychological dissolution found throughout this collection.

Wild at Heart stands as perhaps the most anarchic entry in this collection, with Lynch’s characteristic blend of violence, dark humor, and surreal imagery. Yet it shares with the other films an interest in characters who exist outside conventional society, whether by choice or circumstance.

Taste of Cherry approaches this outsider status from a profoundly different angle. Kiarostami’s meditative masterpiece follows a man driving through the hills around Tehran, seeking someone to help him with a final act. The film’s minimalist approach – long takes, natural lighting, real-time conversations – creates a contemplative space that stands in stark contrast to the more stylized works in this collection, yet shares their interest in characters grappling with fundamental questions of existence.

What unites these diverse films is their commitment to cinema as a form of visual poetry. Each director uses the medium’s unique properties – its ability to manipulate time, space, and perception – to explore internal psychological states that might be difficult to express in other art forms.

The careful attention to color, composition, and rhythm in films like In the Mood for Love creates meaning that exists beyond dialogue or plot. Similarly, the fragmented structure of Memento becomes a metaphor for how we all construct identity from incomplete information. Taste of Cherry‘s patient, observational style transforms the Iranian landscape into a canvas for philosophical reflection, proving that cinema’s poetry can emerge from the most naturalistic approaches.

These films suggest that cinema’s greatest power lies in its ability to preserve moments of intense feeling and make them eternal. Whether it’s the devastating final shot of In the Mood for Love, the cyclical structure of 2046, or the backwards progression of Memento, each film grapples with time’s passage and our desire to hold onto fleeting experiences, and to ourselves.

I’ve chosen these particular films because they understand cinema not just as entertainment. They view it as a means of exploring the deepest questions of human experience: How do we love? How do we remember? How do we make meaning from the chaos of existence?

These are films that reward multiple viewings, revealing new layers of meaning with each encounter – much like memory itself, they become richer and more complex over time.

“The cinema,” said André Bazin, “substitutes for our gaze at a world more in harmony with our desires.”