Probably jeans and t-shirt but i would be very worried because this would mean the world had turned into a very dark place.

The relationship between fashion and totalitarianism reveals itself in how authoritarian regimes consistently target personal expression through dress. Consider how the Nazis required Jewish people to wear identifying badges, or how Mao’s China pushed everyone toward identical blue and gray uniforms. These weren’t just practical policies – they were deliberate erasures of individuality that made dissent and difference immediately visible.

Totalitarian systems understand that clothing is one of our most intimate forms of daily self-expression. When you control what people wear, you’re not just regulating fabric and color – you’re regulating identity itself. The uniform becomes a constant reminder of the state’s power over the most basic aspects of personal choice. It eliminates the small daily acts of creativity and self-determination that keep individual spirit alive.

Fashion, even in its most mundane forms, represents a kind of micro-democracy. When you choose your morning outfit, you’re making decisions about how you want to present yourself to the world, what mood you’re in, what activities you’re planning, even what weather you’re expecting. These tiny choices accumulate into a larger sense of agency and personal autonomy.

Authoritarian regimes also weaponize dress codes to create and enforce social hierarchies. The Khmer Rouge’s black pajama uniforms weren’t just about conformity – they were about breaking down previous social distinctions and creating a new order where only party loyalty mattered. Similarly, school uniform policies in their most extreme forms can prefigure more serious restrictions on personal freedom.

Perhaps most insidiously, fashion control works because it feels so trivial that resistance seems petty. Who wants to die on the hill of wearing colorful socks? Yet history shows us repeatedly that these “small” freedoms often serve as canaries in the coal mine. When societies begin restricting personal expression in dress, it’s frequently a precursor to much more serious erosions of liberty.

The psychological impact runs deep too. Getting dressed each morning is an act of self-creation, a daily ritual where we compose ourselves for the world. Remove that choice, and you’ve damaged something fundamental about human dignity and self-worth. The enforced sameness creates a kind of learned helplessness that extends far beyond clothing.

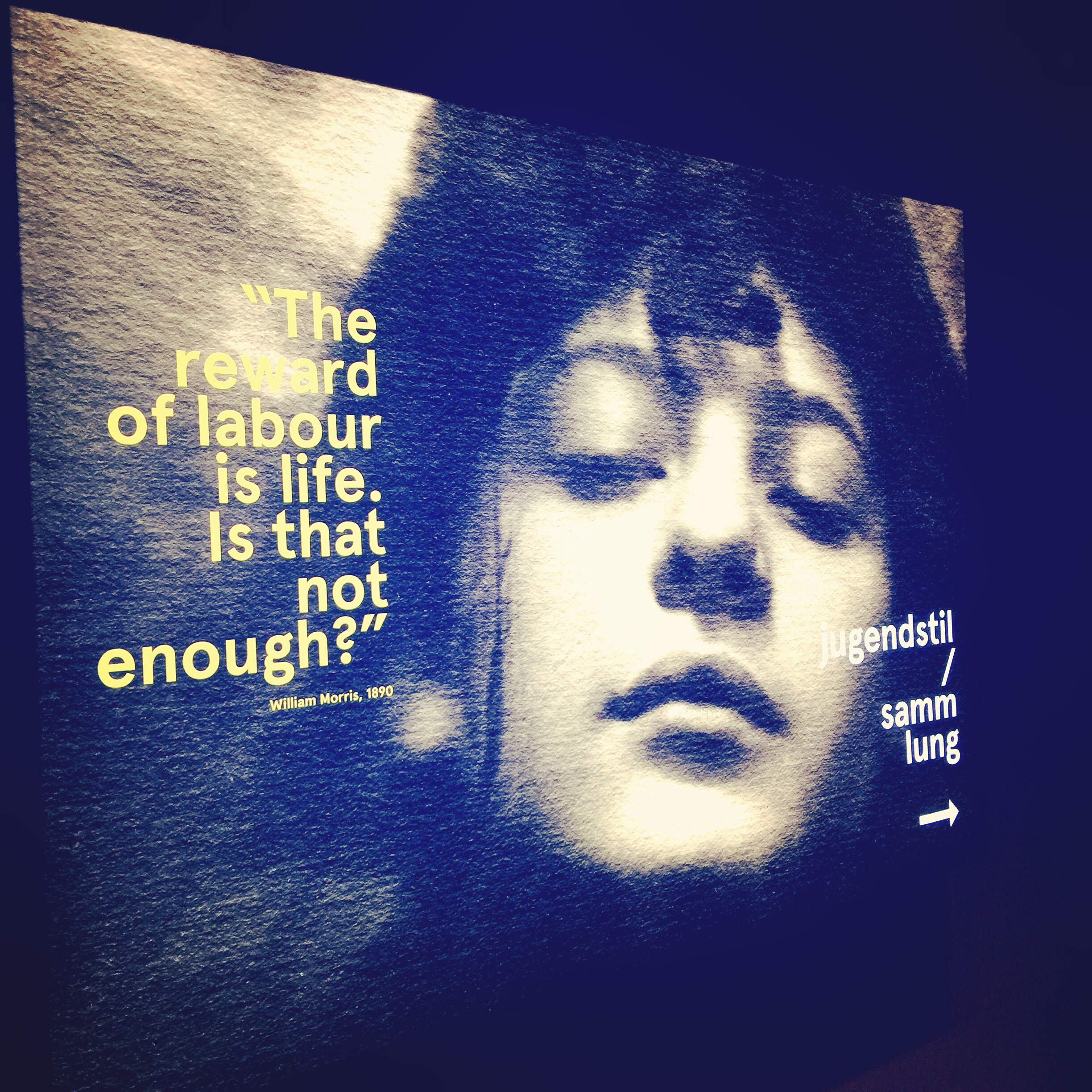

The relationship between fashion and totalitarianism becomes even more chilling when we examine its manifestations across history, literature, and film. These examples reveal how clothing control operates as both symbol and instrument of oppression.

Historical Examples

The interwar period saw a proliferation of “shirt movements” across Europe Shirt Movements in Interwar Europe: a Totalitarian Fashion – fascist groups that expressed their ideology through colored uniforms. Hitler’s Brown Shirts, Mussolini’s Black Shirts, and Franco’s Blue Shirts weren’t just practical clothing but visual manifestos of authoritarian identity. These uniforms served multiple purposes: they created instant group identification, intimidated opponents, and transformed political rallies into military-style displays of power.

Nazi Germany provides perhaps the most systematic example of fashion as totalitarian control. The regime didn’t just require Jews to wear yellow stars – it regulated clothing across society. The Hitler Youth had specific uniforms that emphasized conformity and militaristic values. Women were encouraged to abandon cosmetics and “foreign” fashions in favor of traditional German dress that supported Nazi ideals of motherhood and racial purity.

In Mao’s China, the blue and gray “Mao suits” became virtually mandatory, erasing centuries of Chinese sartorial tradition. During the Cultural Revolution, wearing anything remotely Western or colorful could mark you as a counter-revolutionary. The uniformity wasn’t accidental – it was designed to eliminate visual markers of class, regional identity, and individual taste.

Literary Explorations

George Orwell’s “1984” remains the most powerful literary examination of totalitarian clothing control. In Big Brother’s regime, Winston Smith lives “a sordid dehumanized life devoid of all the traditional sources of happiness” Slavery in Modern Clothing in Orwell’s 1984 – Crisis Magazine, and clothing plays a crucial role in this dehumanization. The Party members wear identical blue overalls, while the telescreen constantly monitors even the most private moments of dressing. Julia’s small act of rebellion – wearing makeup and fixing her hair – becomes a revolutionary gesture precisely because it asserts individual identity against the state’s demand for uniformity.

Margaret Atwood’s “The Handmaid’s Tale” uses clothing as a central metaphor for totalitarian control. The red robes and white bonnets of the handmaids aren’t just uniforms but symbols of reduced humanity – they transform women into walking wombs while stripping away personal identity. The color coding extends throughout Gilead society: blue for wives, green for marthas, creating a visual hierarchy that makes resistance immediately visible.

Ray Bradbury’s “Fahrenheit 451” explores how even subtle conformity in dress reflects deeper intellectual conformity. The firefighters’ uniforms with their salamander symbols and the identical leisure wear of the general population mirror the mental uniformity the state seeks to impose.

Cinematic Representations

Film has powerfully visualized fashion’s role in totalitarian control. Fritz Lang’s “Metropolis” (1927) presciently showed how clothing could divide society into rigid castes – the identical work clothes of the underground laborers versus the elegant fashions of the surface elite.

More recent films like “The Hunger Games” series use fashion as a central element of totalitarian critique. The Capitol’s obsession with extreme, ever-changing fashion contrasts sharply with the drab, practical clothing of the districts, illustrating how fashion can become both a tool of oppression and a symbol of decadent excess.

“V for Vendetta” demonstrates how uniform iconography can be reclaimed as resistance – the Guy Fawkes masks transforming anonymous conformity into anonymous rebellion.

Subtler Controls

The most insidious examples often involve seemingly voluntary conformity. Corporate dress codes, school uniforms, and social pressure to dress “appropriately” can prefigure more serious restrictions. Even democratic societies wrestle with how much clothing choice to allow – from debates over religious dress to workplace appearance standards.

The psychological impact appears consistently across these examples. When totalitarian systems control clothing, they’re not just regulating fabric – they’re conditioning minds to accept that the most intimate daily choices aren’t really choices at all. The person who accepts that the state can dictate their morning wardrobe has already surrendered a crucial piece of mental autonomy.

What makes these historical, literary, and cinematic examples so disturbing is how they reveal the progression from small restrictions to total control. It starts with “reasonable” regulations – safety, unity, tradition – and gradually expands until the very concept of personal choice in appearance becomes foreign. The uniform becomes not just what you wear, but who you are.